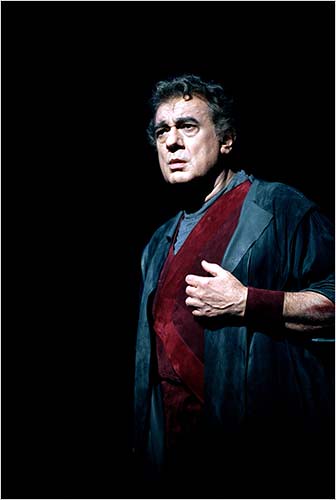

(Renée Fleming)

Na gala comemorativa dos 125 anos do Met, Renée Fleming interpretou um dos seus cavalos de batalha, Glück, das mir verblieb, da ópera Die Tote Stadt (Korngold).

Com cinquenta primaveras, Fleming mantém uma frescura e elegância vocais absolutamente invulgares.

Desde o crepúsculo de Cheryl Studer – mid 1990 – que não escuto uma voz tão pueril, graciosa e elegante como a de Renée Fleming. A mais bela voz do mundo lírico contemporâneo. Sem hesitação alguma.

No final da ária – clicar aqui -, o primeiro a não se comover que se acuse!

E quem não chora não é bom pai de família. De antologia.

A vida pode muito bem iniciar-se aos cinquenta!

Depois deste momento tão eloquente e grandioso, quem se atreve a dizer o contrário?